Women are hauling, lifting, bending, reaching, pushing, and pulling more than their weight serving as over half of the total U.S. workforce. According to reports in Time, Forbes, and the Wall Street Journal, women now make up 50.4 percent of workers. Studies show that statistically speaking, they’re at least as likely if not more likely to be at risk for injury. For too long, the exoskeleton industry has treated women like the second string or an afterthought, asking them to be happy with a one-size-fits-all approach; and trying to fit them into unisex devices that more often than not were designed for and work better for men.

It’s time for this to change.

I’ve spent the last 5 years deeply involved in the development, testing, and implementation of occupational exoskeletons to support hardworking men and women, across a range of industries. About 90 percent of this time was as an industrial ergonomist working with some of the largest logistics and retail companies in the world, and the most recent 10 percent has been as the Director of Ergonomics and Human Factors at HeroWear, which develops lightweight exosuits to support and protect workers. In this time, I’ve tried on over 35 different occupational exoskeletons, and I’ve fit these same devices onto more than 250 workers, both male and female. I’ve seen their reactions: the thrill of assistance, the frustration of discomfort, and for women the common confusion over whether a device was actually designed with them in mind or what precisely to do with a rigid component in the middle of their chest.

The simple truth is that for anything that is designed to be worn, form is just as important as function. In nearly every case, the average female body’s physical makeup is extremely different from the average male. This means women have different shapes and different dimensions to consider for static fit. Women have subtle differences in how they move their bodies, they have different friction points, and different points of sensitivity to consider for dynamic fit. From my experience, men and women often also differ in how they perceive exoskeletons, how they change their behavior to work with the devices, and how their attention and cognition is impacted by the exoskeleton.

Women in the Workforce

Women are our mothers, our sisters, our spouses, our friends, our colleagues, and our role models. They make up a greater percentage of our caretakers, healthcare providers, providers of essential services, and our children’s educators. Women are increasingly side-by-hard-working-side with their male counterparts in the American and global workforce.

Figure 1: Women now make up more than 50 percent of the labor force. (Source: https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-force-participation-key-facts)

Job sectors that have historically been dominated by women are growing, such as the service sector, education, and healthcare, while many sectors historically dominated by men such as manufacturing and mining are on the decline. Women are playing a greater role in jobs historically dominated by males, such as logistics, transportation, manufacturing, mining and logging. Women are also earning more than half of college and graduate school degrees. It’s clear that women are going to continue to play bigger and bigger roles in all industry sectors and workplaces.

Women’s increasing role in the workplace is not confined to private industry, either. It’s also increasing in our military. According to Pew Research, in 2017 women represented 16 percent of the overall active duty force, up from 9 percent in 1980 and just 1 percent in 1970. The percentage of female officers has steadily increased since the 1970s. In 1975, 5 percent of officers were women, compared to 18 percent in 2017.

Women are out there in the front lines, doing the same heavy lifting as men, and enduring the same or higher physical demands. Evidence from military research is clear, showing that women are at a higher risk for injury compared to men. The Marine Corps Force Integration Plan Summary released and reported by Eyder Peralta from NPR in 2015 found that women were injured at more than six-times the rate of their male counterparts, with a significantly higher percentage of these injuries attributable to tasks requiring movement under load. A study on British Army forces (O’Leary et al. 2020) found similar results, with women having a higher incidence of injury in officer, infantry and standard entry training than their male counterparts.

Women appear to have a high risk of injury in industrial sectors as well. A 2009 study in the U.S. found that women have a higher incidence of injury in the heavy manufacturing sector than males (Taiwo et al. 2009). A 2015 Australian study found that women have a higher rate of musculoskeletal injuries than men when the researchers adjusted for occupational group which indicates that the types of jobs being performed by women matter when it comes to the risk for injury, with more physical jobs carrying a higher risk (Berecki-Gisolf et al. 2015). A 2019 study by the National Council on Compensation Insurance found that men have higher injury frequency than women, but that the gap is shrinking (Coate 2019). The reason the gap is shrinking is again because more women are doing heavy physical labor and taking on jobs that have been historically male dominated. With women taking on more jobs in general, including more physical jobs and active military roles, their need for ergonomic solutions to reduce injury risk is paramount, or else this gap will continue to shrink, if not reverse, as more women suffer from musculoskeletal injuries attributable to all the heavy lifting and physical demands.

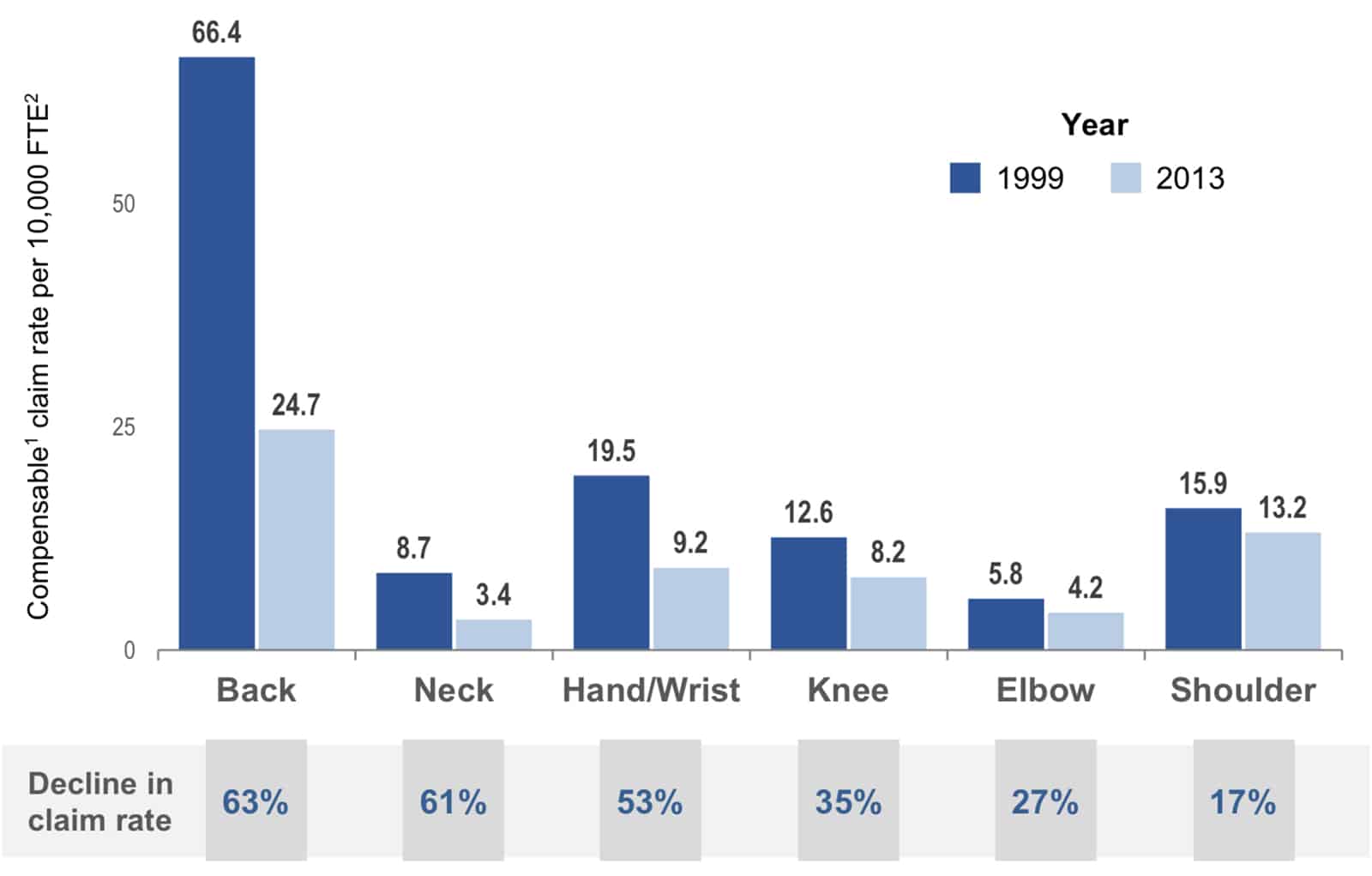

Ergonomics has played a significant role in reducing the rate of injuries over the past couple decades. Various high-risk jobs have been redesigned or automated; engineering and equipment controls have gotten better and more efficient; robots have taken over different heavy and highly repetitive tasks; companies have implemented comprehensive programs which have reduced physical demands and risk for many workers; and companies and militaries have both made significant investments in training. At the same time, the average age of the workforce is growing older, and workers are more overweight and less healthy than ever before on average. The ergonomist’s utopian vision of all high-risk jobs and tasks being redesigned to be safer is not the reality. Despite our best efforts, we will never be able to eliminate all the jobs and tasks where people need to bend, lift or work overhead; so back and shoulder injuries will continue to be persistent problems in the workplace.

Figure 2. Injuries for all body parts have been on the decline. Despite the decline, back injuries are still the most prevalent, and the rate of decline in shoulder injuries is lagging all other body parts. (Source: WA State Dept of Labor & Industries Safety & Health Assessment & Research for Prevention (SHARP) Publication: 76-06-2017 http://www.apps-public.lni.wa.gov/safety/research/files/stats/76_06_2017_wmsdclaimsandcosts.pdf

The military has been researching, developing and testing exoskeletons for decades with the goals of improving soldier performance, and reducing injury risk in both combat and support roles. Occupational exoskeletons came onto the scene around 2014 to support and assist industrial workers, and they have been slowly and carefully tested and implemented by early adopters such as automotive, aerospace and logistics companies ever since. Occupational exoskeletons are also applicable in the military for support roles such as the logistics work of moving food, water, supplies, and ammunition around the globe. With the growing number of women performing these jobs, exoskeleton developers need to take a careful look at the gender shift across industry sectors, the growing percentage of females performing the physical jobs for which exoskeletons have been designed, and ensure they are designing products to fit the female anatomy.

How Current Exo Technology Serves Women

For exoskeleton developers, the most important differences are anatomical and kinetic. Women are shaped differently than men—they have more breast volume, a wider pelvis, are typically curvier in form, approach movement differently and on average have less muscle bulk, and are more flexible.

Shoulder-assist exoskeletons with their more backpack style approach work fairly well for both genders in some cases, but there are good reasons why female-specific hiking and backpacking backpacks are popular with women. The straps, belts and contours of female backpacks differ from male versions to better fit the shapes and sizes of female shoulders, backs, and hips.

Rigid back-assist exoskeletons have been more challenging for women to accept and use in the workplace due to their chest plates, rigid structures anterior and lateral to the torso, and their design around the pelvis, hips, and thighs. Despite some good attempts to make unisex devices more comfortable for women, the chest plates and rigid torso structures compress very sensitive tissues, and women don’t appreciate having to move their breasts out of the way to accommodate the exoskeleton. This is something I heard time and time again as an industrial ergonomist. The hip belts often ride up on the curvier shape of the female pelvis while walking and during repetitive bending and lifting. This results in the entire device shifting upward and the chest plate coming uncomfortably close to the neck. Tightening the hip belt to try to prevent this results in more discomfort around the hips. The angle between the pelvis and thighs (known as the Q-angle) is also very different for females than males. On average, women have a greater Q-angle than males. The hip joints and thigh plates of certain back-assist exoskeletons that only allow for movement in one direction have a tendency to shift toward the outside of some women’s thighs due to their Q-angle. The problem is that the majority of exoskeletons were not originally designed to fit or accommodate the female body – and women know this.

There is another overlooked challenge with all exoskeletons but especially back-assist devices for women. Ask any woman where she sweats first, or where she sweats the most, and she will probably point to her chest. Male and female users alike sweat more in the areas of the body that are in contact with the exoskeletons. Many women are already self-conscious about sweating. Putting a chest plate on the part of the body that many women will agree they already sweat from enough is a significant user acceptance and adoption barrier. All of these factors combined contribute to discomfort, the exoskeleton shifting on the body, distraction, wasted time, poor user experience, and—in some cases—refusal to use the exoskeleton.

A New Way Forward

As exoskeleton technology creeps closer and closer to broader adoption, it’s time to reconsider designing unisex devices.

And yet, at the time of this writing there are no exoskeletons on the commercial market that are designed specifically for women. Fortunately, this is about to change. There are some developers who believe that women should be considered from the very beginning of product development. These developers are designing female-specific and male-specific versions of their products. I’m proud to be a part of one of these organizations, HeroWear, that is committed to serving and supporting men and women alike. I’m proud that we are launching what we believe is the world’s first exoskeleton or exosuit product available in both female-specific and male-specific versions.

Women are now the majority of our industrial workforce. Their numbers and influence are increasing in the military. Women are doing the same work as men in greater numbers each year. And women are getting injured doing it, which will continue into the foreseeable future – unless we do something. Our mothers, wives, sisters, daughters and friends will continue to work hard, fuel our economy, and be leaders. They’ll bend, lift, haul, and reach to do it. They need ergonomic and assistive technology solutions to keep them safe, injury-free, and energized at the end of a long workday. Women make up the backbone of society, and exoskeleton developers have a golden opportunity to protect their backbones. Exoskeleton technology has undeniable potential to be part of the solution to preventing injuries, improving performance, and reducing fatigue for both men and women. As with men, women deserve safe, reliable, effective, and comfortable exoskeletons that are designed specifically for them when they are working hard to support their families and protect their country.

This article is dedicated to my grandmothers, mother, mother-in-law, wife, daughter, and female friends. Thank you for all of your love, support, and inspiration.

By Matthew Marino, PT, MSPT, CPE, CSCS, TSAC-F, a founding Partner of the ASTM Exo Technology Center of Excellence, and co-owner of Prime Performance LLC. Matt has over 20 years of experience in rehabilitation, health and fitness, ergonomics, and the design, testing, use, and implementation of wearable sensor and exoskeleton technologies (LinkedIn)

Matt – Thank you for sharing your exceptional expertise and insight from your perspective as a physical therapist and ergonomist . . . as well as a son, grandson, husband, father, and friend to women! You are a tremendous advocate for the advancement of exoskeleton implementation to support workers and reduce injuries across a wide realm of industries. Looking forward to seeing the ‘cannot be denied’ future innovations that will further empower women to use exoskeletons for work, rehab and recreation!

[…] how intensive physical activity can fatigue the body. He also understands the importance of ensuring that the exosuit and its utility are built with inclusive design practices. “Wearables are going to change the way we work and live, and we want to improve safety, health […]